Class is a term that defines the ranking of people in a society based on their income.

The concept of rich versus poor is one of the most discussed themes in Michael Ondaatje’s novel, In The Skin of a Lion. Toronto, at the turn of the century, had three categories of social class, which were the upper, working and lower class. The term, middle class, did not exist at the time. Middle-class citizens gradually evolved from the working class later in the century after a long industrial development period. There was also no vast difference between the working class or the lower class at that time. Ondaatje, in his novel, focuses on the comparison between the working class and the upper class, so that will also be the main focus of this study. However, instead of focusing solely on Toronto, this study will also reference the entirety of Canada and North America.

The working class at the turn of the century in Canada, particularly Toronto, were mainly immigrants and a few native citizens. Most of these men did not understand English and needed a job to survive; hence their working conditions were deplorable. From their wages to their health condition, none was adequately sufficient. Plus, the jobs available for these working-class men were mostly challenging labour tasks like construction, factory hands, lumbering, etc. Yet they only made between $400 to $500 annually, while taking into consideration that at that time in the United States, it took a minimum income of $600 for an individual to live comfortably for a year (“Working Conditions in Factories (Issue),” n.d.). Ondaatje, in his novel, illustrates horrible conditions of work through his characters, Patrick Lewis and Nicholas Temelcloff. Both men did life-threatening jobs; even the death of Patrick’s father, Henry Lewis, was due to his risky job that involved dynamite, serious explosions, heavy material and equipment that cause injuries at any given time.

A real-life depiction of terrible conditions for those in the working class is the construction process of the Canadian Transcontinental Railroad. The government wanted a railway that could aid in the transportation of people, goods and services and labourers were employed to take up the work. Most of the construction workers who executed this job were Chinese immigrants, and their working conditions were terrible, the same as depicted in Ondaatje’s book. Although the Chinese workers played a crucial role in building the western part of the railway, they earned between $1 and $2.50 per day (The University of British Columbia, n.d.). Making that amount meant that their annual income was between $365 and $912.5. Overall, this was quite a good income considering the minimum amount needed to survive a year but some underlying conditions made this impossible for the Chinese workers. The workers had to pay for their onsite meals, uniforms, transportation, mail, medical care, and they still had to send money back to their homes. All these commitments made it difficult for them to live comfortably on the salary they got (The University of British Columbia, n.d.). Hence the Chinese workers starting taking the most dangerous jobs on camp to earn more money, which led to numerous deaths. This real-life event exactly mirrors the case of Nicholas Temelcloff in Ondaatje’s novel. He executed the most dangerous job on the construction site and got the best pay among the workers, similarly with the dyers from Ondaatje’s story. They got the highest income because their work was hazardous for their health. Berton Pierre’s book, The Great Railway, narrates the detailed misfortune of some Chinese workers. On one occasion, a foreman named Miller forgot to give his crew a warning of the coming explosion, and the blast blew a worker’s head right off, leaving the others to run for shelter (Berton, 1974, p. 296 – 298). Today it is said that for every foot of the Canadian Transcontinental Railroad, a Chinese worker died. It was that bad for the working class, and although it might have been more severe for foreigners, the natives experienced their equal share.

workers during the construction of the Bloor Viaduct

workers during the construction of the Bloor Viaduct

Chinese workers during the construction of the transcontinental railroad

Chinese workers during the construction of the transcontinental railroad

In a working-class family, every member had to contribute, both male and female, including children, because the minimum amount needed for survival mentioned earlier was on an individual basis, not on an entire family. An old study by Michael J. Piva claimed that an average family required $31.83 per week to $1,6555.29 per year to rise above the poverty line. Now the adult male worker earned only 75.6% of the amount mentioned, and this reduced as the years went by to 63.5% (The Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol 13. 1980, p. 521). Therefore for the working family to live comfortably, everyone member had to get involved. Typically, women would work in wool factories or work as maids for upper-class families. The men did heavy jobs similar to the examples mentioned in the third paragraph. The children usually did any odd job they could find.

In most cases, children performed tasks that adults could not accomplish. A good example was mining, where they had to crawl through small tunnels that could not be accessed by full-grown individuals. This particular issue of child labour was not common in North America, but it shows the risks members of the working class took to survive. Most women, while working in the wool industries would suffer serious health complications. For example, they could gradually lose their hearing or even cut their fingers due to the poor condition of the machines used in factories. These women were paid little, worked long hours, and hardly compensated in the case of loss.

image of the tunnel children had to crawl through

image of the tunnel children had to crawl through

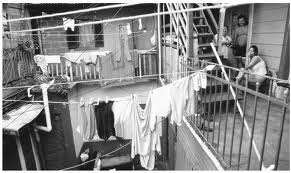

Members of the working class also had deplorable living conditions both on-site and at their homes. Their homes were usually cheap single rooms, which were constantly damp. The environment was always noisy and dirty, with up to 10 houses sharing one toilet. The houses were also compacted, causing a lack of fresh air or water. Plus, there were the constant outbreak of diseases and little access to sunlight. The members of the working class that were immigrants left their comfortable life in cottages as farmers and moved to industrialized cities in hopes of a better standard of living, but it was not as promised. In an article by Hobsbawm in which he analyzes various arguments for the standard of living during the industrial revolution, he stated that the standard of living in cottages was far better than that of factory workers because the environment was secure psychologically satisfactory. However, development was stagnant (Hobsbawm, 1963, p.128). This argument shows that even on the sites where people worked, their living conditioned was nothing compared to the country lifestyle. Ondaatje’s novel – In The Skin of a Lion also depicted these poor living conditions through Alice’s room.

working-class living environment

working-class living environment

Little or nothing needs to be described in regards to the upper class because they were the wealthy members of the community. As the community innovators, they had ideas to develop the city of Toronto, and the people who did all the hard labour for their ideas to become a reality were the working class. Michael Ondaatje gives two examples of such people in his novel, namely: Rowland C. Harris and Ambrose Small. On page 43 of Ondaatje’s In The Skin Of A Lion, Nicholas Temelcloff says that Harris’ expensive tweed coat cost more than the combined week’s salaries of five bridge workers. That very statement solidifies the vast difference between the upper and working-class citizens in Toronto at the turn of the century.

REFERENCE:

Berton, P. (1974). The Great Railway. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Inc.

Hobsbawm, E. J. (1963). The Standard of Living during the Industrial Revolution: A Discussion. Economic History Review, 16 (1), 119-134. Doi: 10.2307/2592521

Michael J. Piva. The Condition of the Working Class in Toronto-1900-1921, Review by Almost Tassonyi. The Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 13. No. 3. (August, 1980), p. 520-522. Doi: 10.2307/134718

University of British Columbia library. “Work: Railways”, The Chinese Experience in B.C. 1850-1950. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.library.ubc.ca/chineseinbc/railways.html

Working Conditions in Factories (Issue). (n.d.). In Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. 2000. Retrieved from http://www.encylcopedia.com/doc/1G2-3406401046.html